NAVYPEDIA

Support the project with paypal

Support the project with paypal

Photo

Dreadnought 1911

Ships

Name |

No |

Yard No | Builder |

Laid down |

Launched |

Comp |

Fate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dreadnought | 00, 56, 73 | Portsmouth DYd | 2.10.1905 | 10.2.1906 | 12.1906 | sold for BU 5.1921 |

Technical data

| Displacement normal, t | 18110 |

|---|---|

| Displacement full, t | 21845 |

| Length, m | 160.6 |

| Breadth, m | 25.0 |

| Draught, m | 9.40 deep load |

| No of shafts | 4 |

| Machinery | 4 Parsons steam turbines, 18 Babcock & Wilcox boilers |

| Power, h. p. | 23000 |

| Max speed, kts | 21 |

| Fuel, t | coal 2900 + oil 1120 |

| Endurance, nm(kts) | 6620(10) |

| Armour, mm | belt: 279 - 102, turrets: up to 279, barbettes: 279, decks: 76 - 38, CT: 279 |

| Armament | 5 x 2 - 305/45 BL Mk X, 27 x 1 - 76/50 12pdr 18cwt QF Mk I, 5 - 450 TT (4 beam, 1 stern) |

| Complement | 695 - 773 |

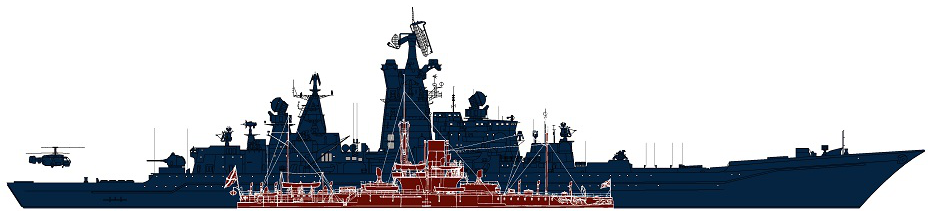

Graphics

Project history

A logical step in British battleship design rather than a sudden departure inspired by Admiral Sir John Fisher. Deadman and Narbeth, who worked on the King Edward VII design had pressed for a heavier armament then and had proposed as all 305mm gun armament for the Lord Nelson class. The Gunnery Branch and DNC's department had already reached the conclusion that a simplified one-calibre armament made sense; gunnery ranges were increasing to the point where 152mm, 234mm and 305mm shell splashes could not be distinguished from one another. In 1904 the USN designers started work on a ship with 4 twin 305mm turrets and no secondary gun bigger than 76mm, for exactly the same reasons, and experience in the Russo-Japanese War would very soon convince the Japanese to go the same way.

Fisher himself does not seem to have grasped the potential for long-range gunnery; what impressed him most about the sketch designs put before him was the economy of maintenance of a ship driven by steam turbines and carrying only one outfit of spares and ammunition. With a programme of increased expenditure planned Fisher was bound to be swayed by the argument that 30 Dreadnoughts would cost the same as 29 Lord Nelsons to run. What was in many ways a much more revolutionary and risky step was the proposal by the Engineer-in-Chief, Sir John Durston, to adopt 4-shaft Parsons turbines. With the backing of the DNC, Sir Philip Watts, the Parsons turbine won the day, despite the fact the first RN destroyers with turbines had only gone to sea four years earlier, the first turbine-driven cruiser was not yet at sea, and the first large commercial turbine-driven ship had not even been laid down.

Designing was very fast, and many mistakes were made. Three distinguished captains agreed to site the tripod mast with its all-important fire control platform immediately abaft the forward funnel, where it would inevitably be smoked out at high speed. This was done merely to provide a convenient method of handling the boats, and taken with some recorded remarks by the Committee of Designs, confirms that neither Fisher nor his appointees had really grasped the implications of long-range gunnery. The same gunnery experts opted for an inconvenient layout of the five 305mm turrets, with two wing turrets which had limited arcs of fire. A more serious weakness was the omission of the upper strake of 203mm armour in previous designs. This was probably done to keep the displacement down, for political reasons, but it meant that at deep load with 2900t of coal on board the draught would rise to 9.46m. At this draught the 279mm belt was completely submerged, and the ship would be protected only by a 1.2m strake of 203mm armour. It was a failing of three designs which followed the Dreadnought, and was contrary to the wishes of the DNC.

When the ship appeared in 1906 her revolutionary appearance stifled such criticism, however, and most commentators were at a loss to understand how a ship of such heavy armament and freeboard had been achieved on only a small increase in displacement over her predecessors. Herein lay the secret of the design, for the steam turbine machinery was about 300t lighter than recipropating engines of the same power. Further-more, the greater weight would have meant bigger engine rooms, and the true saving in weight was probably nearer 1000t. The constructors then contributed their part by designing an efficient hull form to meet the unusually high 21kts speed, using tank models at Haslar to achieve the best form.

The weight of hull structure and fittings was strictly controlled, and the steady reduction in weights which had been going on for a decade or more was maintained. As a result, the hull weight was no greater than the Magestic (1894) despite an overall increase of 3000t. The newer model of 305mm turret and turntable introduced in the King Edward VII also helped to keep weight down. The intention was to build the ship in a very short time, and so the hull structure was designed for simplicity, without losing the rigidity necessary to withstand the shock of eight-gun broadsides. Part of this 'streamlining' was the adoption of standard plates in various sizes and thicknesses. These plates were ordered well in advance. The unpierced bulkheads and separate pumping and flooding arrangements used in the Lord Nelsons were repeated in order to speed construction, although their value in reducing vulnerability was also recognized.

The building of Dreadnought in 14 months set a record which has never been equalled, and although Fisher's drive helped to enthuse everyone connected with the project, most of the credit must go to the staff of Portsmouth DYd. The yard was already the most efficient in the country, having built the Majestic in 22 months and averaging only 31 months for battleships between 1894 and 1904. Once authority was given to divert four 305mm turrets from Lord Nelson and Agamemnon and the way was clear. The keel was laid 2.10.1905, and the official start of trials was 3.10.1906, although the ship not be called complete for another two months.

Sea trials were very satisfactory, as the high forecastle was dry and the full section amidships helped to damp the roll. Above all, the risk taken with the Parsons turbine more than justified itself as vibration was much reduced. Dreadnought gave her name to a new breed of battleship and epitomised the naval arms race between Great Britain and Germany.

Ship protection

Main belt extended at full ship length and was 4.1m deep, including 1.5m below normal load waterline. At 60% of its length, between end barbettes, it was 279mm thick, but thickness of upper 1.4m deep strake was only 203mm. Outside end barbettes thickness of the main belt was decreased to 152mm fore and 102mm aft. Middle deck had 18mm armour steel plating. Main deck in flat part consisted of two layers of armour steel (25+18=43mm), in 3m from the side she was sloped and connected with lower edge of main belt by 68mm slopes (an layer of 25mm Krupp non-cemented armour steel was added). Outside citadel main deck had 38mm thickness fwd and 51mm aft, this deck was risen a little above steering gear compartment and had 76mm glacises. Main 279mm part of the belt was closed by 203mm bulkhead abreast 'Y' barbette between armoured decks.

Barbettes between decks had uniform 102mm thickness, outer semi-cylinders of end and side barbettes above middle deck had 279mm protection, inner semi-cylinders had 203mm plating, 'P' barbette above the middle deck had uniform 203mm protection. Turrets had 279mm faces and sides, 76mm roofs and 330mm rears. Main CT had 279mm sides, its communication tube had 127mm plating, aft CT had 203mm sides and 102mm plating of communication tube. Both CTs had 51mm roofs.

Additional 51mm armour screens were extended from the break of main deck (between the flat and slopes) to double bottom and played role of anti-torpedo protection.

Modernizations 12.

1907: - 3 x 1 - 76/50

1915: lower topmasts were fitted

late 1916: the standard enlarged fire control position was fitted

Naval service

Dreadnought went into reserve in February 1919 and put on sale list in March 1920.

HOME

HOME FIGHTING SHIPS OF THE WORLD

FIGHTING SHIPS OF THE WORLD UNITED KINGDOM

UNITED KINGDOM DREADNOUGHT battleship (1, 1906)

DREADNOUGHT battleship (1, 1906)